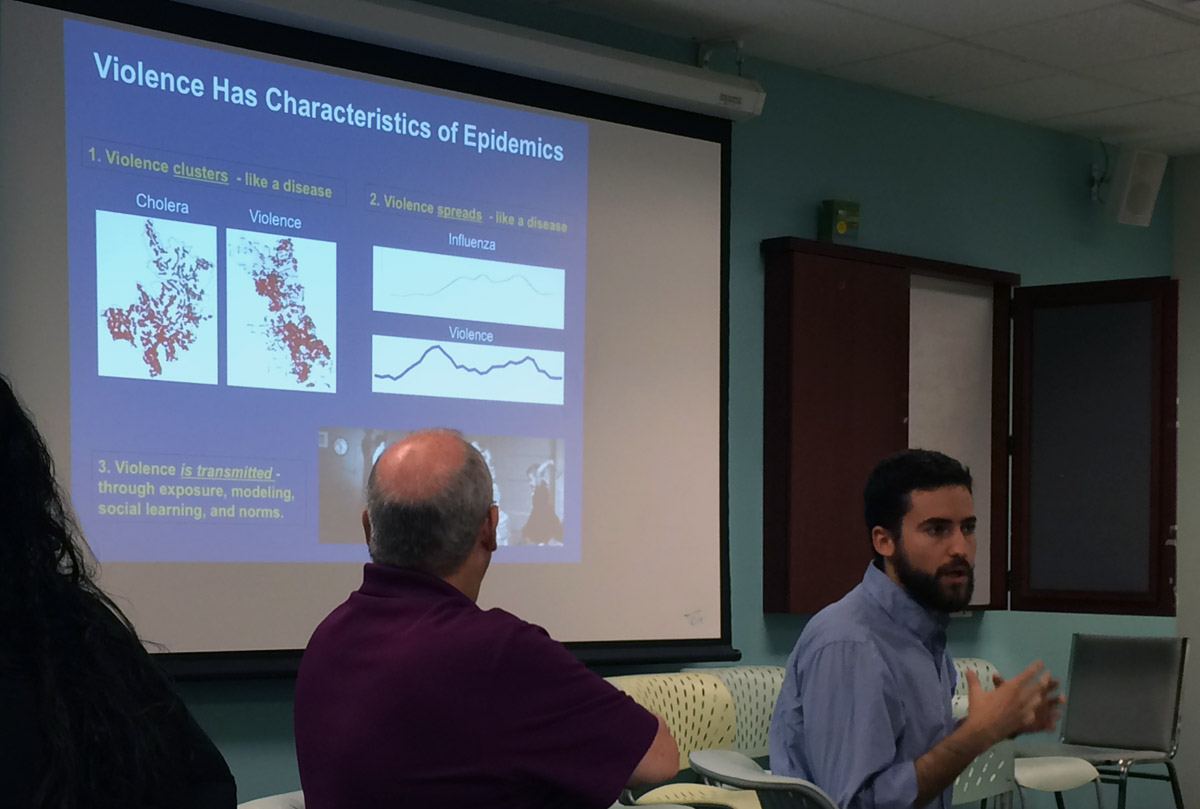

What if we could stop the spread of violence, the same way we prevent the spread of contagious disease?

What if there were evidence-based programs that demonstrated success in curtailing violence?

Here in Baltimore, a program that addresses both of these “what if’s” is Safe Streets.

You can’t have a discussion about what it takes to build a thriving community without talking about safety, so the TCC Steering Committee was excited to have Safe Streets, Cure Violence’s Baltimore partner, come in to present at our September general meeting. For those unfamiliar with Cure Violence, it’s a non-profit committed to reducing gun violence by treating it as a public health issue and addressing it in the same way as you would any contagious disease. The model relies on community members who are carefully selected and trained to intervene in situations where violence is likely to occur. In other words, steps are taken to prevent the spread of violence, in the same way, a community might take measures to prevent the spread of HIV, with interventions that change community norms and behaviors.

Cure Violence isn’t a new concept. It began in Chicago in the mid-1990’s with the Cease Fire program. After demonstrating a 67% reduction in shootings in its first year, the program expanded to several other sites. Baltimore’s Safe Streets program was implemented in 2007 and is now active in five Baltimore communities, Park Heights, McElderly Park, Mondawmin, Cherry Hill, and the newest site, Sandtown-Winchester. Program sites are initially selected based on police posts where homicides are highest.

Notably, Baltimore’s Safe Streets program has been in the headlines lately. A rally was held in early August 2016 to protest $80 Million in cuts the Hogan administration proposed to violence prevention programs including Safe Streets. Fortunately, the Hogan administration reassessed the situation and agreed to provide bridge funding for Baltimore’s Safe Streets program through January 2017, leaving the incoming administration, to figure out a strategy for long-term funding. This tight timing does place the program at risk of a temporary shutdown, but hopefully, long-term funding sources will be identified in time to keep all of the sites fully funded.

What’s ironic, is that the Baltimore Safe Streets program has been proven to be effective. It actually works. In 2015, the Safe Streets program was responsible for 677 mediations; 77% of those involved weapons. That’s over 500 potential weapons incidents avoided. In fact, three of the Safe Streets sites went 365 consecutive days without a firearm homicide. Overall, across all five sites, they recorded a 25% reduction in shootings (with a high of 43% at one of the sites). That’s more than any law enforcement activity. Imagine if we were able to successfully implement this program in every community suffering from high rates of gun violence, just think how many lives could be saved.

In 2015, Safe Streets logged a

25%

reduction in shootings

across all 5 Baltimore sites,

more than any law enforcement activity.

As James Timpson and Dante Barksdale explained in their presentations, reducing shootings isn’t just about reducing the number of guns on the street. In fact, the same gun can be responsible for multiple crimes; it just passes from one person to the next. Additionally, if gang members perceive that there’s been a slowdown in police activity, they may feel it’s a good time to seek retaliation or seek out payments for past transgressions or debts. These types of situations are where programs like Safe Streets can be most effective. When the outreach workers are advised of a potential problem, they can step in to intervene. If it’s after a shooting, they aim to speak to the victim as soon at possible, at the hospital bedside if necessary, to try and prevent any further violence. Importantly, they don’t stop with just the victim of the shooting; they contact other family members, friends and community members — people who might be thinking of seeking retaliation. Unfortunately, retaliation and revenge motivated violence often have no timeline. It can happen days later, weeks later, or even years later. That’s why it’s so important to stem the motivation for violence and help community members to see that there is another way to deal with their problems. It’s about changing attitudes. If someone “disrespects” you, it shouldn’t end in death.

Notably, people whose lives are being saved recognize the value in the Cure Violence Program. This quote from a Baltimore Sun article reflects the perspective of some of the outreach workers and the people they help, “This ain’t about money,” said Safe Streets outreach worker Walter Outlaw, tears streaming down his face. “My life is on the line. … Tomorrow, I don’t know if it’s my last day.”

In addition to literally saving lives by preventing gun violence, the program provides jobs to community members who find it difficult to get meaningful employment. Baltimore’s program employs 40 people, many of them ex-felons or ex-gang members. When you take away supports and jobs like this, there are consequences.

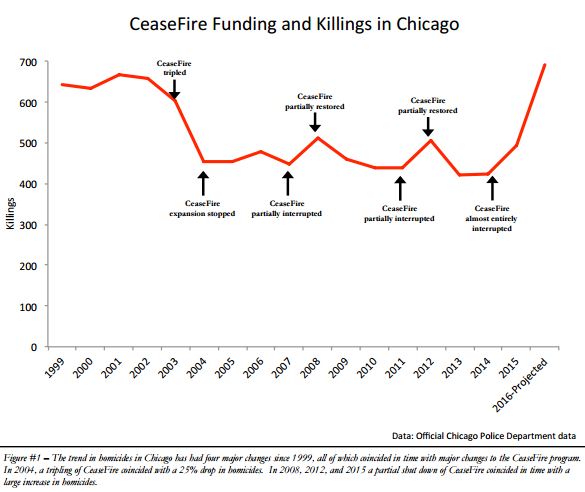

Data from the Chicago program, CeaseFire, offers a good perspective on how effective these types intervention can be, and what happens when they aren’t in place. Over the years the Chicago program experienced multiple cuts in funding, and there is a clear pattern of increases and reductions in violent crime when you reduce and expand funding of the Cure Violence model. The chart below is taken from a September 22, 2016, Cure Violence report on the correlation between CeaseFire funding and shootings and homicides in Chicago. The report states, “… there have been four periods in the past 12 years where killings in Chicago have had a large increases or decreases, and in each case, this shift has coincided with a change in Cure Violence implementation.”

The spike in violence is not something we would like to see happen in Baltimore. Beyond providing jobs and saving lives, there are some economic and social benefits to prevention programs like this. In a 2015 article, The True Cost of Gun Violence, Mother Jones estimated the cost to society of every homicide at $400,000. Unlike other articles that cite the CDC estimate for the medical cost of a Baltimore homicide to be $14,000, their analysis goes on to include the other very real costs incurred.

According to Mother Jones...

“Miller’s approach looks at two categories of costs. The first is direct: Every time a bullet hits somebody, expenses can include emergency services, police investigations, and long-term medical and mental-health care, as well as court and prison costs. About 87 percent of these costs fall on taxpayers. The second category consists of indirect costs: Factors here include lost income, losses to employers, and impact on quality of life, which Miller bases on amounts that juries award for pain and suffering to victims of wrongful injury and death.”

People don’t really want to talk about these taxpayer funded costs, but the reality is they exist. With figures like this, saving three lives a year could justify the $1.2 Million expense of funding Safe Streets’ current five sites, as well as provide an argument for expansion. But, the reality is programs like this aren’t easy to implement effectively, they require time and commitment. At our recent meeting, Safe Streets Program Director, James Timpson explained that one of the keys to successful program implementation is the careful selection and screening of the “violence interrupters” or “outreach workers.” These individuals are community members, typically ex-gang members and ex-felons, with “street credibility.” “We deal with people who carry guns,” James shared, highlighting the inherent risks involved in this work.

Choosing the right people is critical, as these are the individuals who will be responsible for identifying high-risk individuals, connecting them with services if necessary, and intervening to help prevent neighborhood violence. They have to have access to the high-risk individuals, and the credibility that comes from “lived-experience” is invaluable; without it, you simply won’t get access or have influence with the people who are perpetrating the violence.

In an intense environment like this, taking a trauma-informed approach to this work is also important. For so many people, when we hear about Baltimore shootings and homicides, it’s just a number, but for Safe Streets staff, it can often be someone they know. Across the five sites, Safe Streets workers knew 250 of the last year’s homicide victims. That’s a lot of vicarious trauma Safe Streets staff is experiencing, so programs are needed to ensure that the workers practice “self-care.” This can include peace circles, acupuncture, and meditation. Part of the behavior the staff is trying to change is the “tough” street image that negates feelings. They seek to make these self-care practices the “new cool.” Getting staff members to engage in these type of healing practices, takes some convincing, but once they’ve tried it, many embrace its effectiveness.

James and Dante also reminded us that the community plays a role in helping to make Safe Streets work and that how we treat young men of color matters. “When you pull up to a light and lock your door, we know you locked your door.” James shared with the group. “Give these people a face, not a number.” They highlighted that many of the young men they deal with would be happy to get a job that paid $75 per day. When legal choices for income allude them, illegal activity offers an easily accessible path to food and housing.

This was the perfect lead-in to the presentation on the research that went into “Heard Not Judged: Insights into the Talents, Realities, and Needs of Young Men of Color.” Based on nationwide focus group research conducted across seven U.S. cities with boys and young men of color (BMOC) aged 18 to 24, Darryl Cobbin highlighted key findings from the study aimed at 1) identifying the most urgent needs of BMOC and at 2) exploring the viability of an using a branded approach that combined online technology with offline trusted resources to reach and engage this segment. Importantly, this study did not take a top-down approach. Instead, they went directly to BMOCs.

Ultimately, the study concluded that a branded program that took into account the findings from the research and utilized this dual online/offline approach could be extremely effective in helping BMOC to overcome the unique challenges they face which include: getting beyond surviving to thriving, being given an opportunity to leverage their unique talents, and the lack of access to the American Dream. The study highlights many other insights, and they are seeking venture capital funding to help put the program in place. Get access to the full report at www.HeardNotJudged.com.

It would be great if Baltimore decided to invest in a tool to help at-risk youth before they became a statistic — because the price of not acting can end up at $400,000.

To learn more about Cure Violence, check out the video below or watch the full length 2011 PBS documentary, The Interrupters.