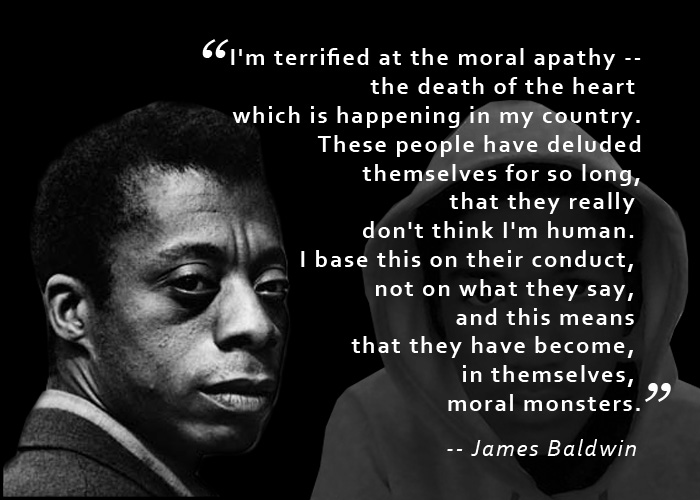

“I’m terrified at the moral apathy — the death of the heart which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long, that they really don’t think I’m human. I base this on their conduct, not on what they say, and this means that they have become, in themselves, moral monsters.”

James Baldwin

1. Paying My Dues

When one speaks of the trauma of racism in this country, there are many ways to see it at work, to witness the destruction and havoc that it wreaks in lives. This film, I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, directed by Raoul Peck, is one of them, even more so because it is no less relevant today than when Baldwin spoke or wrote the passages narrated in the film some 30 plus years ago. This fact, in and of itself, can bring tears to my eyes if I dwell on it, and so I don’t.

I think I truly awakened to the fact that I, and my people, were “still” considered less than human in this country when the verdict came out in the Trayvon Martin case. The ‘not guilty’ verdict lifted a veil that had shielded many in the U.S. from the truth. No doubt, there had been many clues prior to this, but I had conveniently ignored them or dismissed them. I, raised by middle-class parents, in a loving environment, had that luxury. Now, these clues come at us like bullets, every month, every week, every day — almost incessantly in this new era where political correctness is no longer en vogue.

It is in this climate that this film emerges. Raoul Peck, through the words and works of James Baldwin, is able to get to us in the same way that Trayvon did. Baldwin’s unabashed ability to get at the “truth” of who we are as a nation is what’s on display in this film — the sheer oppressiveness of the trauma that racism inflicts and the fact that virtually none who live here are untouched by it.

And once one is awakened to this tragedy, a response is in order. How we choose to “pay our dues” or ignore them, is a question we all must answer.

I have to admit that I saw the film twice and had seen the video segments of Baldwin speak many times before, and yet I remained mesmerized by the utter honesty of what was being portrayed on the screen. The film cloaks us in this heaviness, this trauma, this tragedy that is racism. As Baldwin aspires to tell the stories of the deaths of his friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Dr. King, we feel his pain and his heartbreak at having to bury them — his outrage that yet another life was stamped out by this moral monstrosity that is America.

As I watched, I couldn’t help but to ask the question, because this is our history, is it also our destiny? It reminded me of another film, from the Raising of America series, DNA is not Destiny. I wondered, can this be true of America, that this racism, so deeply engrained into our DNA, doesn’t have to be our destiny?

I think this film, I Am Not Your Negro, offers some solutions. I want to talk about them under some of the same categories as Peck does in his film. I began with “Paying My Dues” and will move on to “Heroes.”

2. Heroes

Enter…the Loving, Caring Adult

Working in the field of trauma and resilience, one of the things we learn about protective factors is the importance of a loving, caring adult in the life of a child. As a gay, young black man, coming of age in the 1940’s in America, there is no doubt that Baldwin must have had these influences in his life. Otherwise, how would he survive?

One of these individuals is highlighted in the film. One of his elementary school teachers, Bee Miller, was a young white woman who introduced him to “the world”—to plays, literature, geography, films — all at the young age of ten.

This made me think that genius is often recognized and supported; but who will be there for those of us who are labeled ordinary? Who will be there to bestow upon them the attention that enables them to overcome, to thrive, to grow beyond the boundaries of Park Heights or Penn North?

Perhaps it is you, and if it is you, are you ready to take on the challenge?

Art as Reality or Reality as Art

There is a segment of the film that explored how blacks are portrayed in films. This is discussed in contrast with how whites are portrayed. Back in Baldwin’s youth, there was a dearth of positive role models. Blacks were relegated to the roles of field hands or janitors. Whites were the cowboys who took their vengeance and were rewarded; they were the films’ winners.

Although now, there are many more positive role models for young black boys and girls, research suggests the preponderance of media about blacks is in fact, negative. Stereotypes continue to persist. Too many of our leaders refer to our youth as “thugs.” Blacks are associated with words like poverty and crime. Many of us believe we are immune to the media, but we are mistaken. As human beings, we are influenced by our environment. And so it begs the question, what can we do about it?

We can start by reshaping the environment — by talking, reading, and writing about real heroes.

Fight against stereotypes. Ask questions. Stop supporting media that depicts the black community negatively. Stop supporting media that idolizes “white saviors.” Recognize that entertainment at any cost is self-inflicted harm.

3. Witness

Baldwin saw his role in the movement as a “witness,” as one placed there to record and report on what was happening. When trauma is exposed in all its ugliness, we are forced to deal with it — to either accept it or to change it.

What’s your role? When you witness acts of racism or other types of trauma, what do you do?

Do you challenge it? Do you observe it? Do you ignore it?

Be a part of the solution. Apathy can be just as dangerous as ignorance.

4. Purity

This segment was devoted to the bifurcated nature of America’s public versus private lives. The Puritan heritage in this country spills over into our lives even today, even into the title of this film. Peck, in the naming of the film, had to make a choice between what Baldwin actually said, and what our delicate ears/eyes/pocketbooks would accept. Our politicians scream of outrage publicly about the same things they partake in privately. Our reluctance to deal in an honest way with sexuality results in misogyny.

One of the tenants of trauma informed care is transparency. If we, in fact, lived our proclaimed values, perhaps we would be a more honest nation, ready to deal with the aftermath of our moral monstrosity.

Under this new presidency, it seems that “purity” has stepped out of vogue. But when we take a closer look, that’s not really the case. We still embrace the lies. Our dollars talk, and, as Baldwin points out, we can’t seem to deal with much true reality. We still have our modern day “Doris Days.” The Obamas were in fact strictly held to and evaluated based upon this “Doris Day” standard of behavior, yet they were still guilty of being black.

As we live our lives, in our families, in our workplace, it is essential that we strive for honesty and transparency… not purity.

5. Selling the Negro

Baldwin points out the historical, economic reliance of this country on “the negro.” At its inception it was slavery. We have since transitioned through Jim Crow, and into the prison industrial complex in all its blatant corruption.

“You can’t lynch me and keep me in ghettos without becoming something monstrous yourselves,” Baldwin wrote.

Let’s just replace that word “ghettos” with “prisons.”

Let’s just replace that word “ghettos” with “underserved communities.”

Let’s just replace that word “lynch me” with “slaughter me in the streets.”

I just want to end by saying, if you haven’t yet seen this film, see it. If it is no longer in theaters, seek it out on cable.

It is a portrait of who we are, but not necessarily of who we will be. It is in our power to shift this dynamic. At least, I believe it is. We can’t begin to heal until we suck out the poison — until we face the root cause of the trauma.

America’s DNA doesn’t have to be our destiny.